Periorbital aging involves changes that are multidimensional and multifactorial. Previous discussions have focused on soft tissue changes. Recent literature, however, has shown that changes occur in the bony structure surrounding the eye, which causes a substantial impact on the aging process, especially with respect to volumetric changes. Comprehensive analysis of both soft tissue and bony structural changes are essential. One procedure or technique alone is usually insufficient. Surgical procedures address some aspects of aging but leave many elements untreated. Office-based nonsurgical procedures form an important basis for periorbital rejuvenation including cosmeceuticals, chemical peels, laser and light treatments, neurotoxins, and fillers. Improved understanding of the pathophysiology of aging and technical advancements in nonsurgical techniques has enabled us to achieve better and more comprehensive improvement for our patients.

The eyes are often the first facial feature to show signs of aging. The changes that occur in the periorbital region are multidimensional and multifactorial. Given the important role they play in our appearance and interaction with the world, the eyes are often the reason that individuals seek out professional help for rejuvenation. One procedure or technique alone is usually insufficient. Surgical procedures address some aspects of aging but leave many elements untreated. Office-based nonsurgical procedures form an important basis for periorbital rejuvenation.

Analysis and Pathophysiology of Periorbital Aging

Periorbital aging is one of the biggest challenges we face as antiaging practitioners. Not only do we need to do a comprehensive analysis of the issues facing each of our patients, but we have to be able to accurately communicate all of the challenges to them. Patients often approach the consultation believing that a simple procedure will solve all of their concerns when in fact several procedures are typically required for a partial solution. Computer imaging can be helpful in the discussion but can be limited given the two-dimensional nature of photography. Three-dimensional images may add some additional benefit to the conversation if they are available.

Careful evaluation with attention to all aspects of periorbital aging is essential for a successful outcome and a satisfied patient. Previous discussions have focused on soft tissue changes. Recent literature, however, has shown that changes occur in the bony structure surrounding the eye, which causes a substantial impact upon the aging process. Computerized tomographic studies by Shaw et al. indicate a significant increase in the orbital aperture width and orbital aperture area in both men and women as early as the fifth decade.1 Additionally, the glabellar and maxillary angles decrease, and the pyriform aperture increases with age. The overall result of diminished bony structural support causes soft tissue descent and redundancy and also contributes to pseudoherniation of orbital contents as well as hollowing. Greater understanding and identification of bony changes can provide an opportunity to obtain a better result in some cases but also points out limitations of certain aspects of rejuvenation.

Soft tissue and volume changes also occur as a result of a loss of support of the ligamentous and septal structures of the eye causing the globe to deepen and descend within the enlarging bony orbital socket leading to hollowing and or bulging of the enveloping orbital fat. Attenuation of the skin and muscle resulting from loss of elasticity leads to redundancy and further loss of support for the orbital contents.

Rhytids form as a result of repetitive movement of skin, which is whisper-thin and prone to solar elastosis. Pigmentation deposits can create a darkening of the lower lid skin that may be accentuated by a shadowing effect from bulging orbital fat superiorly as well as easily visible vasculature through the thin skin. Below the orbital rim, subcutaneous fat resorbs and soft tissue descends, leaving a depression below the area of the orbital rim, known as the tear trough, as well as below the malar fat pad. The resultant concavity adjacent to the convexity of the bulging orbital fat and malar fat pad superiorly with the descending cheek mound inferiorly creates an extended nasojugal groove. Above the orbital rim, the soft tissue of the brow is descending as a result of simultaneous orbital bony rim resorption, loss of subcutaneous fat, and skin envelope laxity.

Periorbital Changes and Treatments

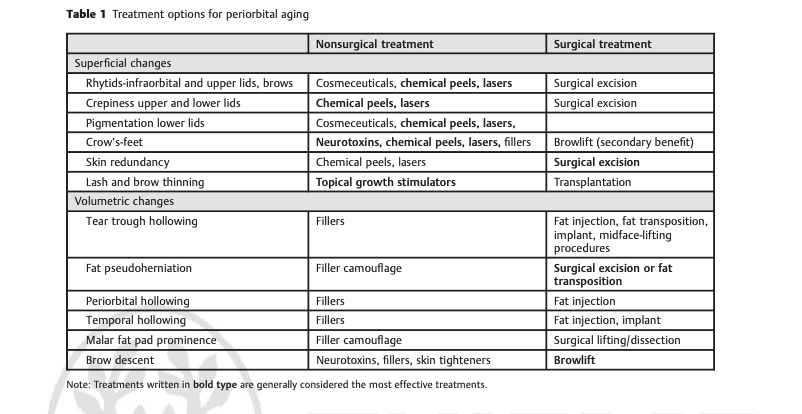

►Table 1 illustrates the importance of both surgical and nonsurgical means to restore a youthful appearance to the periorbital region. The appropriate modality is dictated by the concerns of the patient, the specific anatomy to be addressed, and the judgment and skill set of the practitioner. For the purposes of this discussion, only nonsurgical office-based treatments will be addressed.

Nonsurgical Periorbital Treatment

Skin Changes

Cosmeceuticals are the first line of therapy for antiaging. An effective rejuvenating topical regimen should include a retinoid, α-hydroxy, and/or antioxidant topical product. A hydrating and emollient moisturizer is essential either as a base for the rejuvenating product or as a separate product. Sunblock should be placed at and peripheral to the orbital rim to avoid eye irritation. It is essential that eyelid skin that is extremely thin and delicate ( 100 to 500 μm) be treated with utmost respect. It must remain hydrated and should not be traumatized or irritated. The goal of topical treatment is to reduce the appearance of rhytids, reverse existing actinic damage, and prevent future damage. Great care must be taken not to overtreat with cosmeceuticals or else skin and eye irritation may result. Cosmeceuticals can be very effective if used conscientiously on an ongoing basis.

Resurfacing

Other skin treatments for the eyelid skin include chemical peels as well as laser resurfacing. These modalities can stimulate collagen reorganization, thereby reducing the appearance of rhytids, reducing crepiness, diminishing pigmentation, and possibly tightening skin. The modality of resurfacing should be determined by the degree of damage and extent of aging. The modality must be able to penetrate to the level of damage with the acute awareness that the eyelid skin thickness varies significantly depending on the location being treated. The Glogau scale (broken into four categories, I to IV) can be a helpful way to grade the amount of epidermal and dermal degeneration. Category I is characterized by mild, early photodamage and aging with minimal wrinkles that can be addressed with dermabrasion and/or light chemical peels. Category II damage shows wrinkles that are apparent during movement and requires medium-depth chemical peeling or laser resurfacing. Category III damage includes wrinkles that exist at rest and require medium-depth chemical peel or laser resurfacing on higher settings. Category IV includes deeper wrinkles at rest requiring a deep peel or a more aggressive laser resurfacing procedure as well as surgical intervention in cases where significant attenuation and redundancy exists. For deeper crow’s-feet some practitioners prefer laser resurfacing to a deep chemical peel as they feel they have more control over the depth of injury. Many options exist for light- and energy-based therapy around the eyes. The appeal of these modalities over chemical peeling is the ability to control how much injury is delivered to the tissues and the type of recovery that is desired by the patient. Nonablative treatments typically allow for faster recovery but can necessitate multiple treatments. Ablative treatments such as with erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) or CO2 allow for single treatment sessions with more quantifiable injury but have the requirement of 7 to 10 days downtime during reepithelialization. Erythema can be prolonged over several months and complication rates can be relatively high for complete resurfacing. Fractionation of these modalities has reduced both downtime and the rate of complications while delivering highly effective results. This has become the modality of choice for many practitioners although nonablative procedures remain highly popular with both patients and physicians (►Fig. 1A, B; ►Fig. 2A, B).

Complications of Resurfacing

Resurfacing denudes the skin and thereby introduces the possibility of infection and healing problems, including bacterial, fungal, and viral infections. Prophylaxis with antiviral therapy is a common practice. Some practitioners also prescribe antibiotics as a matter of course whereas others only prescribe them in case of bacterial infection. Dilute vinegar soaks are commonly recommended after resurfacing for their anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial (including antifungal) properties. Inflammation can stimulate hyperpigmentation, especially in darker-skinned individuals, but can be reversed in most cases. More rarely, hypopigmentation can also result from a peel or procedure either due to the destruction of melanocytes or suppression of melanogenesis, which is largely considered permanent. It can occur 6 to 12 months after treatment in some cases. Prolonged erythema can result, lasting for months to up to 1 year. It can herald the development of scarring. Scarring of the thin preseptal skin can lead to ectropion. Steps should be initiated including high-potency steroids, silicone sheeting, blinking exercises, and massage. Ectropion Fig. 1 (A, B) Improvement in pigmentation and fine rhytids after fractional CO2 resurfacing (Lumenis Deep and Active FX-one treatment [Lumenis, Santa Clara, CA]) as well as hyaluronic acid in tear trough. Fig. 2 (A, B) Photo of brows elevated before and after treatment with neurotoxin to forehead, glabella, and crow’s-feet; hyaluronic acid filler in glabella; fractionated CO2 laser resurfacing; as well as upper and lower lid blepharoplasties. Facial Plastic Surgery Vol. 29 No. 1/2013 60 Office-Based Periorbital Rejuvenation Moran can result in severe chronic problems with tear function and exposure. The resultant eyelid malposition can cause significant functional as well as emotional disturbance and correction of malposition is challenging.

Crow’s-Feet

Crow’s-feet result from repetitive movement of the orbicularis oculi causing accelerated breakdown in the collagen and subcutaneous tissues at the point where the skin folds in response to contraction. Neurotoxins are the first line of therapy for crow’s-feet. Quieting the activity of the muscle is essential to preventative treatment of crow’s-feet. Neurotoxins are one of the rare modalities in rejuvenation medicine that can prevent further progression of aging. Relaxing the muscles also creates a therapeutic effect that appears within a few days to weeks. Neurotoxins can create a secondary improvement in the infraorbital rhytids. Deep rhytids can be addressed with fillers; however, the delicate nature of the skin and superficial network of veins makes injecting fillers challenging. It can be difficult to get a smooth result and often patients must tolerate some temporary irregularity and bruising. A lighter filler such as Restylane (Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc., Montreal, Quebec) or Juvederm Ultra (Allergan, Irvine, CA) is preferable if one is to be used. Permanent fillers should be avoided close to the eye, particularly in the mobile region of orbicularis oculi as granulomas may result. Chemical peels and laser resurfacing are often successful in reducing the appearance of periorbital rhytids and, in combination with neurotoxins, are

considered a mainstay for this challenging area. Tightening procedures using nonablative ultrasonic or radiofrequency energy with or without infrared technology can be a helpful adjunct for reducing the appearance of crow’s-feet.

Skin Redundancy

Surgery is the mainstay for reducing skin redundancy in both the upper and lower lids; however, minimal amounts of redundancy can be addressed with chemical peels and laser resurfacing. Tightening procedures as mentioned previously can be effective for reducing skin redundancy. Some of the devices can be used with special adjustments for the thin skin around the eyes. They can also be used to elevate the brows slightly, which can improve upper lid laxity in some cases.

Lash Thinning

Topical lash growth stimulators have opened up an entirely new avenue for eye rejuvenation. Lush, full lashes and brows are a marker of youth and the loss of them is a rite of passage into aging. Women tried many means to enhance what sparse lashes and brows they had remaining with cosmetics, prosthetics, tattoos, and transplants. None of these means gave ideal natural youthful looks. The lash growth products have changed all of that. Many patients benefit tremendously when using these products if used properly and regularly. The prescription product is the glaucoma drug bimatoprost. Bimatoprost and a similar drug, latanoprost, are prodrugs of a prostaglandin agonist, which, in addition to reducing introocular pressure, stimulates lashes to enter the anagen phase of hair growth thereby increasing the number of lashes

growing as well as enhancing their length. Earlier nonprescription versions were based upon bimatoprost. Now, as a result of regulation, most over-the-counter versions contain peptides such as myristoyl pentapeptides that stimulate keratin genes regulating growth.

Volumetric Changes

Tear Trough Deformity

A common development in the periorbital region is often referred to as “dark circles” under the eye. They occur not only as a result of aging, but as a result of various genetic, anatomical, or other environmental issues in patients both young and old. A true tear trough deformity, as first coined in 1969 by Robert Flowers is an anatomical condition that results from attenuated soft tissue overlying the medial third

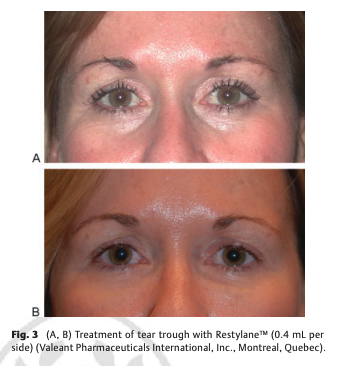

of the inferior orbital rim and maxilla.3 It is bounded by the thin eyelid skin superiorly, nasal skin medially, and cheek skin inferiorly. The tear trough overlies the orbicularis muscle, which is attached directly to the bone. The dark circle effect is often accentuated by pseudoherniation of orbital fat from the medial and middle compartments casting a shadow as well as deepening the appearance of the depression. Additional elements that darken the appearance of the tear trough are the capillary and venous network, which can be easily seen through the thin eyelid skin; pigmentation, which seems to preferentially deposit in this region in some individuals; edema resulting from allergies; or other mechanical forces. Early approaches to the tear trough deformity featured surgical treatments such as midface elevation using suborbicularis oculi fat to camouflage the depression as well as orbital fat transposition. Alloplastic implants have also been utilized. Fat injections have become more popular for this region but require a high degree of skill and experience to avoid irregularities. Increasingly, even the most experienced practitioners have turned to injectable fillers to address this area, specifically, hyaluronic acid. With proper technique, it is effective and affords little downtime and few complications. Furthermore, it is reversible with hyaluronidase in the case of overcorrection, irregularities, or a Tyndall effect. Many practitioners favor the product Restylane due to the smaller size of the hyaluronic acid particles compared with Perlane (Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc., Montreal, Quebec) as well as the predictability of its lower hydrophilicity compared with Juvederm products. There are, however, many practitioners who use a variety of fillers in this region with success.

Technique

Injecting the tear trough can be done with or without anesthetic. Topical anesthesia is not ideal as the skin-plumping effect of the cream or gel can ablate the subtleties of the defect that you are trying to correct. Similarly infiltration anesthesia will also partially “fill” the defect. Nerve blocks can be used effectively if needed. Fortunately, the region is not especially sensitive compared with other areas of the face. It is crucial that the patient is able to be calm and still during theprocedure given the proximity to the eye and the need for Facial Plastic Surgery Vol. 29 No. 1/2013 Office-Based Periorbital Rejuvenation Moran 61 precision. Some practitioners like to dilute the hyaluronic acid product. Using a serial puncture technique and a 30- gauge syringe, hyaluronic acid is infiltrated in the supraperiosteal plane of the tear trough, which is likely also intramuscular given the firm adherence of muscle and periosteum to the bone in this region. Linear threading is preferred by some practitioners. The infraorbital foramen is a tricky area to inject given the vasculature, which, if violated, can cause significant and prolonged bruising that is difficult to camouflage. It also can be a bit of a “sinkhole” for correction while simultaneously being the neediest region for correction in some instances. A “quit while you are ahead” approach is sometimes the best one. The remainder of the tear trough requires microaliquots of filler (0.02 to 0.05 mL per injection)

with constant reassessment of correction and digital massage of each microbolus as needed. The most medial nasal region is the limit to treatment. The skin is very thin and adherent at this point and prone to irregularities. The total volume needed rarely exceeds 1 mL split between both eyes and often can be as little 0.5 mL. Overcorrection is not always apparent at the time of treatment. Fortunately, correction is simple and effective using 5 to 20 U of hyaluronidase. It is best to forewarn patients that they may need up to a week of social downtime because the treatment can result in noticeable bruising. Avoiding blood-thinning agents is strongly advised prior to and immediately after treatment. Cool compresses after treatment and perhaps Arnica montana may help to limit significant bruising (►Fig. 3A, B).

Fat Pseudoherniation

The only treatment for fat pseudoherniation is surgical reduction or redistribution of fat. Camouflage can be obtained, however, using fillers or fat injection. Given the nonsurgical premise of this discussion, only fillers will be described. Fillers have previously been described for treatment of the tear trough region. For the most part, camouflaging the fat pseudoherniation either involves or is similar to filling the tear trough. Not infrequently, fat herniation exists without a tear trough deformity. The region surrounding the herniation appears to be a relative deficit, however, so the technique and approach is very similar. The filler is used to smooth the transition between the convexity of the fat bulge and the relatively lower cheek lid junction.

Periorbital Hollowing

As described earlier, some individuals manifest periorbital aging by hollowing. This can also be a manifestation of prior blepharoplasty with fat removal. Restoration of periorbital volume has been a daunting prospect and remains so for all but the most skilled and knowledgeable practitioners. Fat injections have been successfully used for the last two decades. It is highly technique sensitive. In the last decade, the growing use of hyaluronic acid fillers has made treatment of hollowing more accessible. As with tear trough filling, the tendency is to use Restylane given its predictability. The majority of published experience with filling the hollowed periorbital region addressed the upper lid. This can be combined with augmenting the brow bone since part of the underlying defect is bony orbital resorption. Small aliquots

presented in a fanning motion are typically used.4 Frequent massage to create a smooth appearance is essential given the lack of subcutaneous soft tissue in the region. Injectable fillers in the upper third of the face must be approached with a high level of respect for the possibility of retrograde embolism and retinal artery occlusion. Although the incidence is rare, it is real. A recent review of the literature reported 15 cases of blindness after fat injections.5 There have been two reports of retinal artery occlusion with hyaluronic acid. Other substances reported include paraffin, silicone oil, bovine collagen, polymethyl methacrylate, hyaluronic acid,and calcium hydroxyapatite. Many of the emboli occurred during injections near the nasal dorsum and glabella. Preventative management by using smaller-gauge needles or cannulas, aspiration to confirm a lack of intravascular needle position, low-pressure technique, and smaller volumes can be helpful. Symptoms of sudden blackout and extreme eye pain

are pathognomonic for retinal artery occlusion. Unfortunately, there are no ideally effective treatments to restore vision. If hyaluronic acid is the filler substance, immediate injection with hyaluronidase should be initiated. Emergent consultation with an ophthalmologist is imperative.

Temporal Hollowing

Temporal hollowing typically results from the loss of fat with age. It is an aspect of aging that has more recently achieved attention in part due to increased experience with fillers and fat injections as well as an overall greater appreciation for the volumetric nature of the aging face. Certain medical conditions can also cause or contribute to temporal hollowing. Low body fat due to illness or lifestyle as well as medications can cause extreme temporal hollowing. Regardless of the cause, the treatment is to restore volume. This can be done with any number of the fillers or with fat injections. Some Fig. 3 (A, B) Treatment of tear trough with Restylane™ (0.4 mL per side) (Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc., Montreal, Quebec). Facial Plastic Surgery Vol. 29 No. 1/2013 62 Office-Based Periorbital Rejuvenation Moran practitioners prefer a dilute solution of hyaluronic acid. PolyL-lactic is another popular choice. Some practitioners prefer a longer-lasting solution with an alloplastic implant or dermis. The challenge with injectables lies in avoiding the vast network of veins. A significant amount of volume is often required to fully correct the deformity (e.g., 1 to 2 mL of filler per side).

Malar Fat Pad Prominence

The malar fat pad is an area that is difficult to treat surgically. The malar fat pad seems to be “privileged” fat that remains in place while surrounding subcutaneous fat either disappears, descends, or herniates. It sits above the zygomaticofacial ligament and below the orbital rim and orbicularis retaining ligament. It can create a distinct mound that seems almost out of place and is prone to lymphedema. The depression below the fat pad can be a lateral extension from the tear trough deformity. Patients seeking treatment of their “bags” sometimes are actually referring to the malar fat pad mound. It is important that they understand that the standard eyelid procedure does not encompass this separate anatomical region. Surgical dissection of the pad can be complicated by prolonged lymphedema. Careful placement of filler inferior to the pad to blend with the cheek is an effective means of camouflage, especially when the concavity below the pad is bordered inferiorly by the convex descending cheek mound. The single convexity of a more youthful cheek can thus be restored. Filler choice is not as specific in this application. The plane also varies from superficial to deep (even supraperiosteal) as the individual patient anatomy requires and as the injector sees fit.

Brow Descent

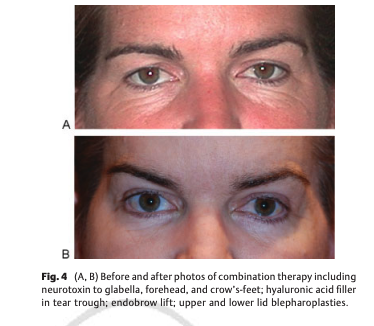

Brow descent occurs early on in the aging process. It causes a tired appearance and contributes to redundancy of the upper lids. Even a few millimeters of descent can create a problem, especially with a shallow orbit. Surgical lifting, both endoscopically and using an open fashion, has been the mainstay of treatment. When the problem is subtle or the patient is not a surgical candidate, neurotoxins have been found to give a “chemical lift” to the brow. This can occur using two methods. By treating the glabella and the midportion of the forehead while leaving the lateral brow and forehead untreated, the unopposed action of the elevators gives a lift to the lateral brow. Care must be taken to avoid the “spiked look.” Another technique is to place a few units at the superior lateral orbicularis to oppose the depressor effect.6 Recent studies have highlighted the resorption of the bony orbital skeleton as a significant contributor to the aging periorbital region. It would follow that augmentation of these bony prominences could offset soft tissue descent. Fillers have been used in the last decade to treat brow descent and

the bony skeletonization that can occur with age. Good results have been obtained with most of the available fillers using a careful fanning approach and small volumes to avoid irregularity (►Fig. 4A, B).7

Summary

There are many options for periorbital rejuvenation both surgical and nonsurgical. To achieve an optimal result, multiple modalities are necessary. Understanding and communicating the fundamental changes happening on the bony and soft tissue level is crucial to success. This leads to a more open-minded and broad approach to the periorbital region that leads to better satisfaction for both patient and physician.

Mary Lynn Moran, MD

1 Private Practice, Woodside, California

Facial Plast Surg 2013;29:58–63.

Address for correspondence and reprint requests Mary Lynn Moran,

MD, 2973 Woodside Road, Woodside, CA 94062

(e-mail: [email protected]).

References

1 Shaw RB Jr, Katzel EB, Koltz PF, et al. Aging of the facial skeleton:

aesthetic implications and rejuvenation strategies. Plast Reconstr

Surg 2011;127:374–383

2 Gilchrest BA. Treatment of photodamage with topical tretinoin: an

overview. J Cosmet Dermatol 2009;8:228–233

3 Hirmand H. Anatomy and nonsurgical correction of the tear trough

deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;125:699–708

4 Lambros VS. Hyaluronic acid injections for correction of the tear

trough deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;120(6, Suppl):74S–80S

5 Lazzeri D, Agostini T, Figus M, Nardi M, Pantaloni M, Lazzeri S.

Blindness following cosmetic injections of the face. Plast Reconstr

Surg 2012;129:995–1012

6 Balikian RV, Zimbler MS. Primary and adjunctive uses of botulinum toxin type A in the periorbital region. Facial Plast Surg Clin

North Am 2005;13:583–590, vii

7 Lambros V. Volumizing the brow with hyaluronic acid fillers.

Aesthet Surg J 2009;29:174–179